The idea is pretty simple. Given the URL to a Youtube video, the script spews out it’s thumbnail. See this lovely image? It would make for a perfect wallpaper and I wrote a script that does just that.

How would Python render it possible, you’d ask? By working hand-in-hand with Youtube API, of course! I should seriously reconsider becoming a clown. I have a hunch that it would come as natural to me. Let’s face it - my nose naturally turns red when it’s cold and my feet are enormously large. Which implies…

Is it by chance an apple pie?

…that they would fit those funky clown shoes just perfectly. Oh, the pie. Right.

API stands for Application Programming Interface. Be prepared for more mumbo-jumbo gibberish down the road. When I use the term, I mean a subset of a service’s funcionality that your script can make use of. The use case covered by this tutorial can be brought to life because Youtube API (the service) provides an endpoint to download the thumbnail given the video ID. Programmatically speaking it’s nothing more than a function. It yields some output (the thumbnail) given some parameters (the Youtube video ID) or lack thereof.

To interact with aforementioned API we are going to use a Google API wrapper - a Python abstraction for the API. It acts like any other library and I believe that it greatly simplifies the task as it doesn’t require performing a HTTP call explicitly.

We are also going to need an API key - our license to use the interface. Here are detailed instruction on how to obtain it. You will be prompted for your project name. In case you were looking for a catchy name, you should be fine with big-potential-216709.

Installing the wraper

The wrapper can be conveniently installed from a CLI using pip - the default Python’s package manager. First we need to create a virtual environment. It has it’s advantages. For example it allows two projects to depend on different versions of the same packages. It’s not necessary, as we could install our packages in global scope, although it’s useful.

Invoke the following command to create the virtual environment in directory venv:

python -m venv venv

Invoke the below to activate the virtual env (I assume that you run it on Windows using Powershell):

.\venv\Scripts\activate.ps1

The shell should now display (venv) in front of current directory:

(venv) PS C:\Uthumer

Run the below to actually install the wrapper:

pip install google-api-python-client

REPL

Seriously, I think that it’s one of the best things about Python. It allows you to test all your crazy ideas in sandbox manner. I always have it open while I work on my code, as it helps me to figure out empirically how a certain method behaves. It also simplifies comming up with an algorithm, as it allows you to examine a code snippet in isolation. The fact that it evaluates your expressions as you enter them (that’s what REPL stands for) means responsiveness and it makes the whole experience enjoyably fluid.

You can invoke it by typing the following command in your favorite shell:

pythonEt voilà! In a moment you will see how deep the rabbit hole goes but for now why don’t we play with it a little? The following snippet of code would make it memorize a value assigned to a variable:

| |

1. Assigning a variable. I’m the guy who documents getters and setters in his code, by the way.

2. An expression to evaluate. Because we reference a variable name, it would get substituted to 5 - the value that we previously assigned to it.

3. Evaluated expression.

Multiline snippets of code are also possible - just press Shift + Enter. Keep in mind that identation is still a necessity. This little conditional statement should print 5 = 5!:

if var is 5:

print('5 = 5!')

I deeply and profoundly love this workflow. I hope that it would charm you, too! We are going to get familiar with it’s real power shortly.

Interacting with the API

When it comes to our little utility, we could use the REPL to get acustomed with our wrapper. Let’s try it out, shall we? As documented on the docs page, we have to import the library first and then use it’s build method to obtain a service object (our wrapper). It takes a couple of parameters, incuding the API key that we have already received.

| |

1. Import the method from the library (note the modified module name) that returns the wrapper object.

2. Specify method parameters.

3. Build the wrapper object using the unpacked api_params dictionary defined before. It equals to the code below:

api = build(developerKey='YOUR_API_KEY', serviceName='youtube', version='v3')

I know, right? Given keyword arguments order is not important, it makes for some flexible function calls. It rocks… until you have to mock it. Or maybe it’s just me?

Great success! You have just builded your wrapper object! Now that we have it, we can use it to obtain thumbnail links. In terms of the API client that we use, videos is the collection that we will be working with. Here you can see full specification of it’s structure, albeit we are only interested in a ['snippet']['thumbnails'] key. It can be obtained through list method. Roughly it would translate to the following Python code:

request = service.videos().list()

Executing the code would raise an exception that we didn’t provide enough parameters to the list method. We are going to handle it in a moment. An example (the 4th one) provided in - lo and behold - the docs gave me an idea what parameters should I pass in order to obtain metadata that interest me. It speaks of the following URL:

https://www.googleapis.com/youtube/v3/videos?id=7lCDEYXw3mM&key=YOUR_API_KEY&fields=items(id,snippet(channelId,title,categoryId),statistics)&part=snippet,statistics

Phew. Let’s break it down a bit and look at it from the Python perspective. Our query consist of a couple of variables:

| |

1. Youtube Video ID.

2. Your API key.

3. Here we specify first level keys which fields interest us. We can further pinpoint them using fields variable.

4. Metdata about video(s) that you are wishing to obtain. They are maped directly to the response fields that you are going to get.

You can easily compare the output with the video utilized by the example. More so, it’s perfectly possible to visit this link using your browser. You would see the following JSON response:

{

"videos": [

{

"id": "7lCDEYXw3mM",

"snippet": {

"channelId": "UC_x5XG1OV2P6uZZ5FSM9Ttw",

"title": "Google I/O 101: Q&A On Using Google APIs",

"categoryId": "28"

},

"statistics": {

"viewCount": "3057",

"likeCount": "25",

"dislikeCount": "0",

"favoriteCount": "17",

"commentCount": "12"

}

}

]

}

Quite obviously the response is not what we were wishing to get, although I think that it gives a rough idea how the API works and how would we use it to get the data that we want. Please, look at our resource representation once again. We are interested in a snippet part because that’s where we can find thumbnails field. Knowing how the previous query relates to the response returned by the API, we should be able to get our thumbnails through passing the following query parameters:

id = 'U-iEK0mlmuQ'

key = 'YOUR_API_KEY'

part = 'snippet'

fields = 'items(snippet(thumbnails))'

Let’s return to our benelovent REPL and see if we are right. The parameters above directly translates to Python code and they could be directly pasted into our interactive console, albeit I’m going to pack them into a dictionary like I did when I had builded the wrapper object:

request_params = {'id': 'U-iEK0mlmuQ',

'part': 'snippet',

'fields': 'items(snippet(thumbnails))'}

request = api.videos().list(**request_params)

The last step is to actually execute our query. In order to do that, we are asked to use the execute method:

response = request.execute()

As I wrote in the previous section, we can access the variable value by simply entering it’s name into REPL:

response

{'items': [{'snippet': {'thumbnails': {'default': {'url': 'https://i.ytimg.com/vi/U-iEK0mlmuQ/default.jpg', 'width': 120, 'height': 90}, 'medium': {'url': 'https://i.ytimg.com/vi/U-iEK0mlmuQ/mqdefault.jpg', 'width': 320, 'height': 180}, 'high': {'url': 'https://i.ytimg.com/vi/U-iEK0mlmuQ/hqdefault.jpg', 'width': 480, 'height': 360}, 'standard': {'url': 'https://i.ytimg.com/vi/U-iEK0mlmuQ/sddefault.jpg', 'width': 640, 'height': 480}, 'maxres': {'url': 'https://i.ytimg.com/vi/U-iEK0mlmuQ/maxresdefault.jpg', 'width': 1280, 'height': 720}}}}]}

Uh oh. Not the most decipherable output, isn’t it? Worry not! We can use lovely json library to make it more human-readable. Try the following snippet of code:

| |

1. Import json library that we will use to receive pretty, formatted output. It’s a part of vast Python standard library, which I find cool on it’s own.

2. Create output string. The indent parameter tells us that each level will be indented using 2 spaces.

3. Print our response on the console.

4. Formatted output.

Much better! In order to make navigating over thumbnails entries a little more convenient, I’m going to assign appropriate key under corresponding variable:

| |

1. I think that navigating over lists and dictionaries in Python is pretty straighforward, although I’m going to explain it a bit for the sake of clarity. The value under items key is a list (think of it as of an array - they behave the same in this example) which is denoted by [ and ] characters. It has only one item and Python list indices start from 0, so by typing [0] we will get what we want. The snippet resource which we reference using a ['snippet'] key contains one more object - thumbnails. There are images URLs that we are going to process.

2. Format dictionary items that we have just extracted using 2 spaces indent.

3. Display our data structure.

4. Formatted output.

Before we can download our image, we need a way to determine which one is the biggest. Thumbnails come in different sizes depending on the video. Documentation for the resource states that it can return them in the following dimensions:

- default (120 x 90)

- medium (320 x 180)

- high (480 x 360)

- standard (640 x 480)

- maxres (1280 x 720)

As you see we have received them all. Unfortunately we can’t just assume that our video comes with all of the above and just download the maxres image. Some of them simply don’t have it. For example an API request for the iconic Charlie bit my finger yields only these:

default (120 x 90)

medium (320 x 180)

high (480 x 360)

standard (640 x 480)maxres (1280 x 720)

Because the sizes returned by the API can vary I decided to find a way to make sure which one is the biggest. The simpliest approach that I can think of is to create an ordered list of sizes and check if the response has returned any of them. I think that I’m okay to assume that I can rely on the default item order, although my inner paranoid yells at me to manually check which image is the biggest based on their dimensions in pixels. He would certainly benefit from an obesity diet, so I’m just going to leave him to starve:

| |

1. Define constant denoting images size order. They correspond with dictionary keys of previously defined thumbs variable.

2. A function that returns an URL of the largest thumbnail based on a dictionary passed as it’s parameter. Returns None if it contains no key specified above. I don’t think that it may happen, but it’s considered to be in good style, isn’t it?

3. Iterate over SIZES keys to find out if thumbs dictionary contain any of them.

4. Check if a currently processed size key is present in thumbs dictionary.

5. Because a key was found, get a value from thumbs dict that matches it and assign it to a temporary thumb variable.

6. Get the thumbnail URL.

7. Return the thumbnail url.

8. Return None if thumbs contain no size key listed in the SIZES.

9. Assign the largest thumb to a thumb_url variable.

10. Display the URL.

Woah! Our first function! Now that’s a reuputable tutorial! Now that we have it, we can finally download our image.

Finally downloading the image.

I’m going to use request module from urllib library to download the image. It comes with a convenient urlretrieve method which is perfect for our use case. I was considering using requests library as it would do the job just as well. I decided to use urllib because it’s a part of Python standard library (which is always a plus if you ask me) and it can download the file with just one line of code using a dedicated function. It’s perfectly possible that requests provide such a method as well but I’m simply not aware of it.

Given that you have been following the tutorial all along, all you have to do is to import the method from the urllib module and invoke it as shown below. It would retrieve the image from the Youtube server and save it under the name specified by filename variable:

from urllib.request import urlretrieve

filename = 'wallpaper.jpg'

urlretrieve(thumb_url, filename)

1. Import the method that would enable us to simultaneously download and save the image.

2. Specify the downloaded file name.

3. Get the image under the URL assigned to the thumb_url variable and save it in the current directory under the name specified by filename variable.

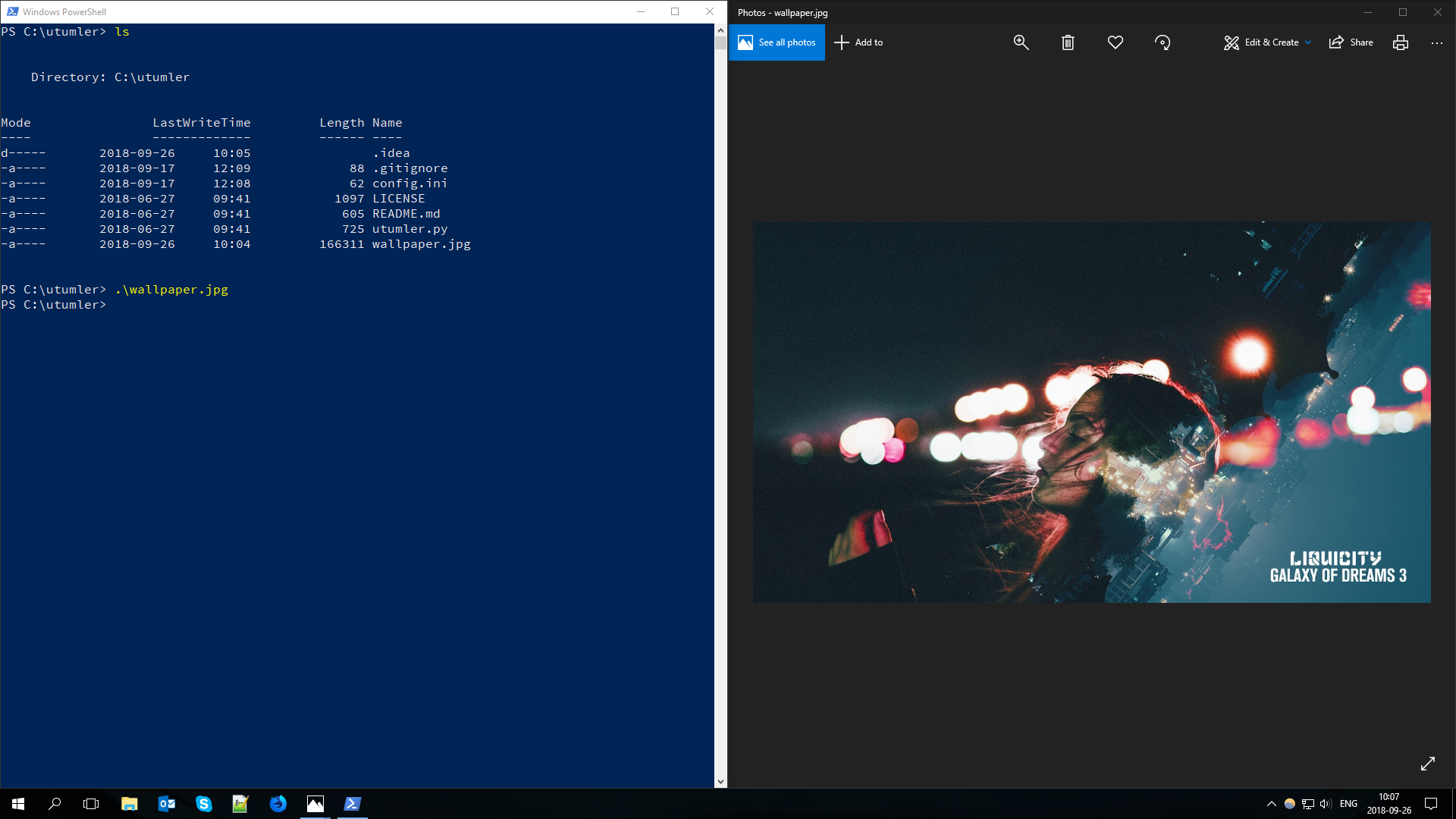

Here it is. The downloaded image in the flesh.

Putting it all together.

I think that would be nice if we saved our progress in a script file. This way we could reuse it in the future. I think that it is very likely given what the script does. Personally I use it on regular basis and I hope that you find it this useful, too!

Despite of you finding it handy, we are going to need the script file later on in order to pass some CLI parameters to it. Here’s everything that we’ve got so far (roughly in the order that we entered it into the interpreter):

| |

Just by looking at it I can’t help but think that we need to immediately…

Refactor it with fire

I love refactoring. As of lately I tend to write a rough draft first and worry about deploying it in methods and classes later on. I find it less streneous than diving right into OOP and whatnot.

First of all I think that it would be nice if we removed test outputs and a reference to the json library as they will be no longer needed.

| |

| |

I think that it would be cool if we put getting the wrapper and obtaining thumbnails from the server into functions. Let’s start with obtaining the API object first. This is the code that bothers me:

| |

It depends on one parameter - your API key (assigned to a developerKey named parameter). Let’s create a function that takes just that and returns a builded wrapper:

| |

1. Our API key. I decided to make it a constant, as I think that it’s unlikely that it’s going to change.

4. Define a function that takes the API key as it’s only positional parameter.

5. Define wrapper parameters. Here we use our API key passed as a function argument, so it’s no longer hard-coded.

8. Build our wrapper using parameters specified before.

9. Return the wrapper.

12. Get the wrapper and assign it to api variable.

Neat! Now let’s take care of receiving the thumbs. This is our little code:

request_params = {'id': 'U-iEK0mlmuQ',

'part': 'snippet',

'fields': 'items(snippet(thumbnails))'}

request = api.videos().list(**request_params)

response = request.execute()

thumbs = response['items'][0]['snippet']['thumbnails']

It would be nice if we passed a video ID as a function argument. We will also need the wrapper object as it is required to execute our request. The refactored function would look like this:

| |

4. Define a function that returns thumbnails for a video given it’s ID and using provided API wrapper.

5. Define API endpoint parameters.. We are going to use a video ID provided as a function argument.

8. Prepare a request that would get our thumbnails list.

9. Execute the query.

10. Extract thumbnails metadata from the response from the server.

11. Return extracted thumbnails metadata.

14. Get extracted thumbnails metadata and assign it to thumbs variable.

There are still a few steps left. As you might have already seen, the code interlaced with functions definitions doesn’t look particularly good. We will eventually put all this in a dedicated class, but I suggest that we start with creating a method that downloads the video thumbnail. This is what we have so far:

| |

As you can see, I have slightly altered the code. I believe that it’s more readable and organized now. I decided to put our SIZES list at the top of the file. I think that this way it would be easy to find if there’s a need to alter it. I have also made the api_key variable a constant and put it next to SIZES list. Additionally all functions definitions are now at the top of the document.

Using the highlighted lines from the listing above, I have came up with an idea for a function that downloads the thumbnail:

| |

1. There are a couple of parameters here. Let’s break them down:

api- as the function references other functions that we have defined before, we have to pass an api object, so that they can be properly invoked.video_id- an ID of a videopath- a path to a saved file. I decided to rename it fromfilename. I have came up to a conclusion thatpathis more appropriate (sadly, appropriatier is not a word), as the file can be saved anywhere on your device. It defaults towallpaper.jpg, which means that the file under that name would appear in the directory where you have fired the script.

2. Get thumbnails URLs for a given video referenced by it’s ID.

3. Get the largest thumbnail URL.

4. Save the image using the path provided as a function parameter.

The last logical step would be to create a class that would wrap the code that we have just written. I think that the class concept is easiest to grasp when defined as a container for functions and variables. In that context the former turns into a method and the latter transforms into a field. Those terms are often interchangeable. Let’s create one!

| |

1. Define the aforementioned class. I have decided to name it Uthumler because it’s a Youtube Thumbnail Downloader. Youtube, hence u.

2. Define a class variable for internal use. Leading underscore basically means that you should not mess with the variable. We will definitely need the Youtube API to perform our query, even if it’s empty for now. We can access it using a dot operator, like so (though not recommended):

| |

1. Create an instance of our class - an object that gives us access to it’s fields and

methods. We do this by using our class like a function. We can pass paremeters to it, but we don’t need them right now.

2. Get the api field value. It returns nothing, as it’s value is None, which literally means that there is no value assigned! Actually it’s value is set to an object of NoneType class, but let’s stay in a fairyland a little bit longer.

Now that we are acquainted with classes and objects, let’s obtain the API wrapper object. We can convienently copy the get_api method that we have written before, with some alterations:

| |

5. An annotation that makes the following method definition a property. More on it below.

6. The method that we decorate. Because we have just used the @property decorator, it has turned into a getter. It allows for the following trick:

| |

1. Create an object of our class.

2. Assign a value of it’s api property to a variable of the same name. Note that while the names clash, there is no conflict because they have different scopes.

3. To make sure that I have ended up with a return value of the api property, I print it’s value using a built-in type function. It returns a <class 'googleapiclient.discovery.Resource'> object, which is exactly what the api property is supposed to return.

It’s only argument is self. It’s an internal reference that allows an object to access it’s own fields and methods that can vary between objects. This documentation article describes it in greater depth.

Let’s put the rest of our methods in our class, with slight alterations:

| |

Highlighted code is going to be executed only when we invoke the script from CLI, as documented here. It wouldn’t be executed if a script is imported as a module (which isn’t our usecase anyways).

We will need one more method to extract video ID from an URL. It may look like this:

| |

1. Our class method that takes Youtube video URL as a parameter.2. Sanitize the URL so it doesn’t contain character we don’t want.

3. Check if it’s a shortened URL.

4. Split the URL on youtu.be/, leaving us with a list that contains our ID on first ([1]) position. This can be checked experimentally using REPL:

| |

7. Display our ID.Config

We are going to implement config using python built-in configparser module. Let’s create a new settings.ini file and put out settings in it:

| |

1. Define a youtube group.2. Add your API key.

3. Define sizes. Since it’s not a Python file, we do not define it as a list per se, but as comma-separated sequence. We are going to parse it in a moment.

Now we need to refactor Uthumer class to introduce the changes:

| |

3. Here we create an object of ConfigParser class. Since we don’t use it for anything fancy, we don’t need to pass any variables to it.9. Use API key saved in an API_KEY key of youtube settings group.

18. Split sizes list on a comma. It returns a Python list like we used before.

Done! Python abstractify configs really well. We needed only a few lines of code to achieve what we wanted.

CLI

Adding CLI functionality is pretty straightforward, too. Modify the script like so:

| |

3. Import needed library.9. Create a parser object and add custom description to it.

10. Add an url argument to the parser.

11. url help message.

12. url default value if not passed.

13. Get arguments.

14. Get url from the arguments.

15. Run code if url has been passed. Default argparse error message will be displayed if no url has been detected.

16. Get video ID using the method that we created before.

17. Download the thumbnail.

Final words

The tutorial is over. It came lenghty for a problem this simple. I think that it will make it appeal to beginners better. I made such thing for the first time and I wanted to pour all my knowledge into it. I hope that you enjoyed it!